[ad_1]

As he stood at a lectern earlier this month to discuss his department’s efforts to “protect communities from violent crime and the gun violence that often drives it,” U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland rattled off a list of cases his office was pursuing against people who are alleged to have bought guns for themselves and then sold them to others.

In one, a person bought 92 guns from a licensed dealer that were eventually used in crimes, including homicide and drug trafficking. In another, Garland pointed to a 12-person gun trafficking conspiracy that moved more than 90 guns across state lines into Chicago. They were later linked to mass shootings, multiple deaths and injuries.

“We have instructed our federal prosecutors and law enforcement agents to prioritize prosecutions of those who are responsible for the greatest gun violence,” Garland said. That includes “those who illegally traffic in firearms and those who act as straw purchasers.”

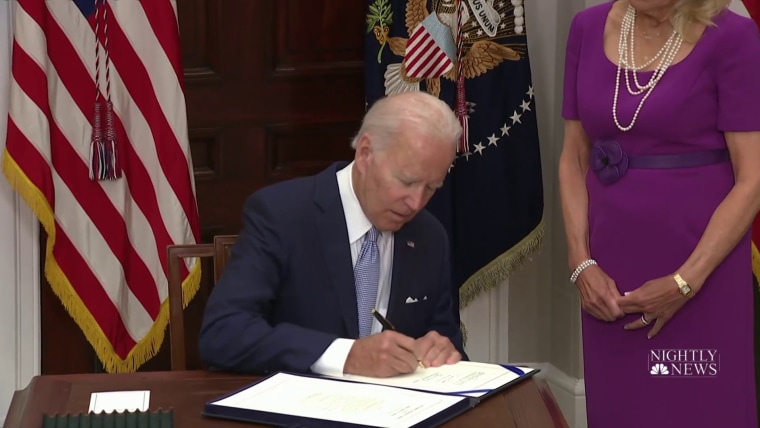

His office may soon get some help on that front. There is optimism that two lesser known provisions in the bipartisan gun legislation that President Joe Biden signed into law last week will put a dent into the illegal flow of weapons bought through straw purchases and potentially expand the responsibility of gun sellers.

The first provision clearly defines straw purchasing — or when a person asks or pays a surrogate to buy a weapon for them — as a crime. It puts in place a severe penalty as well: Up to 15 years or 25 years when tied to drug trafficking.

The straw purchasing element was largely apolitical, three people close to or involved in the bipartisan negotiations said, but it could have a huge effect.

“By creating federal straw purchasing trafficking offenses in this law, we’re definitely giving prosecutors the teeth they need to target straw purchasers and illegal gun runners,” said a congressional aide, who requested anonymity to speak candidly about the negotiations. “Our intention here was to stop things like the flow of illegal guns into cities that have stronger gun laws from states that don’t.”

‘Following a trail of blood’

Prior to this legislation, buying a gun for someone else amounted to little more than a paperwork violation and proving that someone knowingly committed a crime could be difficult, two former agents of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, who worked on straw purchasing investigations, said.

Prosecutors had to show that buyers were purposefully lying when they bought the gun from a dealer and always intended to give it to someone else to get a conviction. The two former ATF agents said it didn’t always make for the most compelling cases.

“Convincing a federal prosecutor to pursue these charges and spend their valuable resources on what amounted to a paperwork violation is difficult,” said one of the former agents, Joseph Bisbee, who served in the ATF for 25 years.

Bisbee said investigators had better luck when they pulled together a group of purchasers into a case and showed some element of organized crime, but even then the effort could feel like a waste.

“The penalties involved were pretty minimal,” he said. “In a way, that made a lot of sense because for a straw purchaser to go into the gun dealer and buy the gun, they had to be able to pass a criminal history check. And so they didn’t really have a criminal history.”

The lack of a clear penalty is one reason that the agents believed this method of acquiring weapons has been commonplace since at least the 1990s, when the ATF started more thoroughly tracking straw purchasing cases.

Joseph Vince, another former ATF agent, recalled a first-of-its-kind study in the 1990s that attempted to track how criminals chose to acquire firearms. That convinced him that straw purchasing was the main culprit and should be the target of law enforcement if they want to avoid “following a trail of blood,” Vince said.

“Looking at the data, and the data evolved into millions of guns, the No. 1 way criminals acquire guns is through straw purchases,” the former agent added. “It makes sense: if you want a hamburger, you go to McDonalds; when you want to get a gun, go to a gun store — it’s just so easy.”

Who is a gun seller?

The second provision makes a potentially large change with very few words.

It modifies the definition of “gun seller” from a person who sells guns with “the principal objective of livelihood and profit,” to anyone who sells a gun to “predominantly earn a profit,” thereby widening the pool of potential gun sellers.

In the past, Bisbee said agents like himself were often left unsure whether they could target certain sellers for peddling guns without a license if they weren’t operating something as clear as an official storefront. He said the agency was often left sending “sternly worded letters” to warn individuals who were private sellers or selling guns out of their homes because they didn’t necessarily have the enforcement power.

While the three people close to the bipartisan negotiations tempered expectations that this could close the “gun show loophole” or have a significant effect on the sale of guns online, they believed it could be a significant step toward creating an extra layer of enforcement and oversight of a market that operates with limited supervision.

They said that they had in mind the Midland-Odessa, Texas, shooter who killed eight people in 2019 with a gun that he bought through a private sale. He had previously failed a background check from a licensed gun seller and was not allowed to buy a weapon.

“We’re really putting these sorts of sellers on notice that if you are selling guns predominantly for profit, you need to be running background checks,” an aide close to the negotiations said.

This would be a step past “sternly worded letters” for ATF and potential enforcement, said Rob Wilcox, the federal legal director of Everytown for Gun Safety, who consulted with Democrats on the legislation.

“This kind of clarity by Congress gives ATF the ability to tackle the kinds of commercial marketplaces where you have individuals who are selling a dozen guns a year or more either online or at gun shows without background checks,” he said.

Still, some still expressed skepticism about how far-reaching the law could be.

Lindsay Nichols, the federal policy director at Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, said that the changes were rather minor and that without larger modifications and increased funding for agencies like ATF, there would be little difference on the streets.

“Unlicensed sellers would still not be required to conduct background checks and there would be really limited change in terms of who has to get a license,” she said. “This really just codifies something that courts have already interpreted the law did, so it doesn’t really expand the scope.”

[ad_2]

Source link

More Stories

The Georgia runoff looks very tight – politicalbetting.com

Wells Fargo Active Cash Card Review

Pele: Brazil legend says he is ‘strong with a lot of hope’